This essay is based on an interactive workshop given at the Swan Lake Nature House in Saanich, BC on Oct. 13, 2023.

Grieving Our Aloneness

Philosopher David Abram mused that the West is a civilization that has been increasingly talking to itself for the several hundred years. In so many ways, the mainstream of Western cultures have disenchanted the world and tuned out the hymn of praise that is being sung from its heart. This isolation is sometimes referred to as the modern malaise, a loss of meaning and purpose in what is felt to be a vast, godless cosmos. It is no wonder that so many of us feel a sense of longing and grief that is sometimes hard to place.

Biologist Paul Shepherd in Talking on the Water said, “The grief and sense of loss, that we often interpret as a failure in our personality, is actually a feeling of emptiness where a beautiful and strange otherness should have been encountered.” This quote appears in Francis Weller’s book The Wild Edge of Sorrow, where the author begs us to apprentice ourselves with the hidden pain in our hearts and of the world. As we Westerners move to re-enchant our worlds, we are sheepishly coming back into conversation with the earth community, which according to our science from the last 200 years, is merely driven by the laws of matter, chemical reactions and biological urges. For this reason, as Weller writes,

“…the perennial conversation has been silenced for the vast majority of us. There are no daily encounters with woods or prairies, with herds of elk or bison, no ongoing connection with manzanita or scrub jays. The myths and stories about the exploits of raven, the courage of mouse, and the cleverness of fox have fallen cold.”

Much of our grief for the world comes not from an inner imbalance, but from an outer absence from the web of life that make up our day-to-day worlds.

Tuning in, learning to listen again, witnessing the pain and joy of the world, and collaborating in a vast conversation is essential for these troubled times. We must, as Robin Wall Kimmerer admonishes, re-learn the grammar of animacy that exists in so many Indigenous languages. She writes,

“It’s no wonder that our language was forbidden. The language we speak is an affront to the ears of the colonist in every way, because it is a language that challenges the fundamental tenets of Western thinking—that humans alone are possessed of rights and all the rest of the living world exists for human use. Those whom my ancestors called relatives were renamed natural resources. In contrast to verb-based Potawatomi, the English language is made up primarily of nouns, somehow appropriate for a culture so obsessed with things.”[1]

The materialism of the West developed with and through our noun-based languages. Our lives and our tongues have been stripped of vibrancy, animacy and aliveness.

Fostering Ecological Dialogue

Western cultures are waking up to the rich chatter of the natural world in ways that were lost to us for half a millennium of mis-enchantment by our anthropocentric theologies and sciences. We are connecting with the ancient wisdom preserved by Indigenous peoples, rural people, and many ethnic and esoteric knowledge systems that have existed underground and on the margins within Western cultures.

In recent years, forest ecologist Dr. Suzanne Simard has made headlines for claiming that trees communicate through a neural-like web of root grafts and mycorrhizal networks. Though her work has come under fire in recent months for overstating this claim, she articulates a widespread intuition shared by many of us and reinforced by popular works from foresters like Peter Wohlleben or biochemist Diana Beresford-Kroeger. This intuition is that trees are more than natural objects that can be valued either as so many board feet of timber or for their intrinsic aesthetic beauty. Simard writes, “Our modern societies have made the assumption that trees don’t have the same capacities as humans. They don’t have nurturing instincts. They don’t cure one another, don’t administer care. But now we know Mother Trees can truly nurture their offspring.”[2] Trees are alive and they’re talking!

Trees seem to communicate as much with each other as with their fungal partners. Mycorrhizal fungi enter the very cells of trees and trade sugars for water, nutrients and information. A healthy and resilient forest is one that has a web of connections and dialogue partners. Despite being competitive when it comes to canopy real estate, trees have been documented sharing resources with other trees, especially kin, but also between species such as Douglas fir and Paper Birch. Trees can also communicate above ground. Some trees that are being attacked by defoliating insects, for example, release a pheromone that can be “smelled” by adjacent trees, queuing them to up their chemical defenses.

This awakening on the part of Western cultures and sciences to the amazing complexity of forests has got me thinking. How might we humans (of immigrant and settler backgrounds), learn to better listen to the conversations of the more than human world? And more specifically, what kinds of dialogue partners could help us discern a more reciprocal, relational and regenerative place in the rapidly changing ecologies of the so-called Anthropocene, an age of expanded human impacts on the earth community?

While it is certainly the case that we should continue to demand ecological justice, biodiversity protections, and an extreme reduction in carbon emissions, we are now at the point where reductions will almost certainly have to be paired with removal. This might mean that our children will come of age in a brave new world of geoengineering experiments and a global network of carbon vacuum plants.

Of course, planting trees is certainly an important activity and part of the solution, but with slow growth rates and their susceptibility to becoming carbon sources due to their pesky flammability, any carbon forestry should probably be nested within wider ecological and common good goals, rather than being integrated into market-based offset initiatives. In other words, we should plant trees because planting trees has a range of ecological and cultural benefits apart from the hyped quantified economic or climate benefits.

To these two general points—couching our ecological actions in dialogue and increasing tree-covered landscapes for a range of values—I want to start a conversation with a tree that has witnessed the entirety of human evolution across the globe. I am speaking of, and to, the mighty oak tree.

A Love for Oaks

I grew up with an orange tree in the back yard, and our neighborhood streets were lined with Eucalyptus windrows. The oranges migrated from southeast Asia via Spain, and the Eucalypts directly from Australia. Orange County, a sleepy network of agrarian villages, eventually enlisted a narrow band of fruits in a botanical get rich quick scheme where they now grow mostly high-end houses and luxury malls.

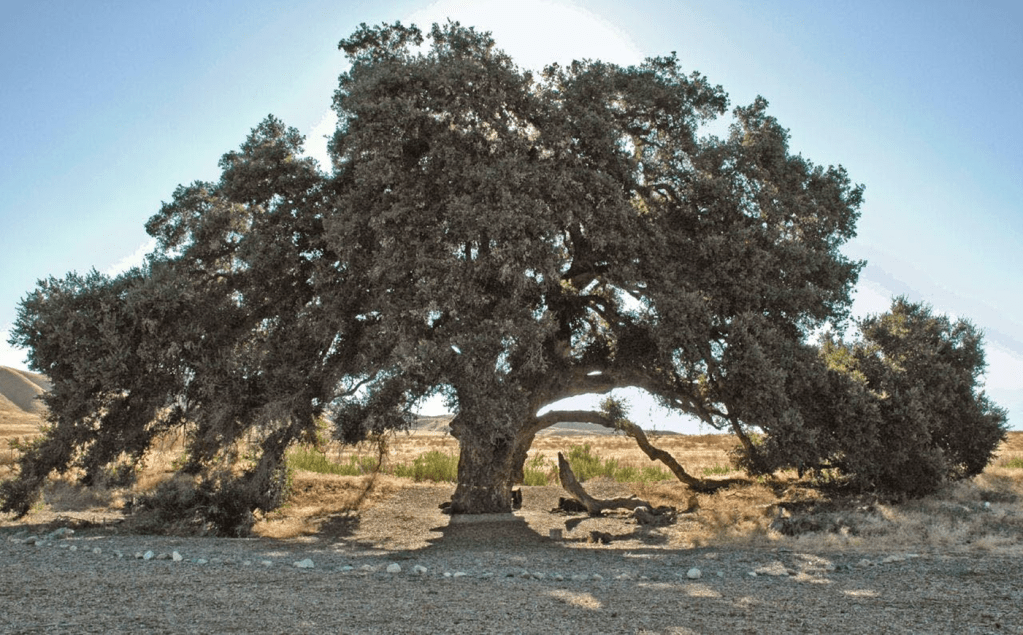

Despite this charismatic flora, I will never forget the dusty smell and dappled light of the patches of preserved oak woodlands that were the destination of naturalist programs and school field trips. California boasts nearly 20 oak species, and the California Live Oak (Quercus agrifolia) was a common oak in protected areas and patches of undeveloped foothills inhabited by lurching dinosaur-shaped oil rigs. The Live Oak’s glaucous holly-shaped leaves and slender charcoal-colored acorns spoke to me of an ancient way of life. A way of living in this place that my people had never really been interested in learning. And so, the oak whispered softly in the background of my childhood, and most of my arboreal memories are of foraging lush oranges, feral figs, and blood red pomegranates from the shaggy suburbs of Yorba Linda.

When I lived in Utah, I met the Gambel Oak (Quercus gambelii) who lived in the foothills below the alpine fir forests. It is a scrubby oak that dwells in clusters and thickets and rarely grows taller than 10 meters. They are expertly fire adapted, and quickly regrow from their vital roots. They are a stable food source for bears, turkeys and deer. And Indigenous peoples of the Wasatch range and great basin harvested them regularly for food which was even used as an aphrodisiac by the Isleta Pueblo.

When I moved to Connecticut for forestry school, I worked for a summer at the Yale Forest in Northeaster Connecticut. The hardwood forests of Connecticut are home to at least 13 Quercus species. As foresters, we were attempting to manage the forests so that they would retain oak in perpetuity. Because oak trees need more light than maple trees, selection harvesting of choice oak trees can shift the forests species composition toward more shade tolerant species such as maples. To ensure that oaks would be in the next generation, harvest plans not only needed to ensure that there were enough oak trees in the canopy left to provide acorns, but also that there was enough room in the harvested forest floor for the oaks to germinate and thrive. I loved my time in the forest, and even though we marked for cutting some hefty oaks, we left behind many more, and opened space for the next generation to grow.

In 2014, I spent a month living with the monks of Our Lady of Guadalupe Trappist Abbey in Carlton, Oregon. I was there preparing for my doctoral dissertation which would study the sense of place and ecological spirituality of Catholic monastics. The 1,300-acre property had been clear cut in the 1950s and the monks spent many decades reforesting their steep hill with Douglas fir plantations. In the 1990s however, the abbey underwent an ecological paradigm shift. They wanted to manage the forest more sustainably, and more in line with the local ecology. They hired a talented local forester who wrote a new management plan for the abbey and began diversifying the abbey’s forests. One project he proposed was a full-scale restoration of the Oregon White Oak (called Gary oaks in British Columbia) savannas that used to be in abundance in western Oregon. After some persuasion the monks agreed, and the abbey now boasts several hundred acres of grasslands dotted with majestic oak trees. I have visited the abbey many times over the years, and I always enjoy reunited with both my monk and oaken friends.

Oak as Provider

Oaks are in the Beech family, Fagaceae. Globally, there are over 500 oak species, with Mexico and China being countries with the most species. Oaks evolved over 56 million years ago with the emergence of flowering plants. Oaks predate humans by millions of years, and by the time humans emerged, oaks had wrapped a green embrace around the temperate northern hemisphere.

Oaks are a loquacious species. They have associated with dozens of fungal partners including truffles. One source identified over 800 insects that are associated with the oaks, 48 of which were obligates. These obligates include the visible gall wasps which hijack to oak leaves to create a swollen outgrowth from which young wasps emerge sometimes gall oak apples. Mammals and birds also love their acorns which are a staple food for many diverse forest ecosystems.

In 1985, David A. Bainbridge coined the term Balanocultures. Balano is the Greek word for acorn, and Bainbridge argued that what in Asia and the Mediterranean were assumed to be mortar and pestles for grinding grain, in fact predated the widespread domestication of grains. Bainbridge suggested rather, that across the temperate zone, oak and oak ecosystems were the primary food system of our budding old-world civilizations.

Forest lands have always been multiuse spaces where game, cultivation and harvesting happened simultaneously. From the earliest archaeological accounts, fire was used as a management tool. Many forests containing oak, hazel, and chestnut were burned to maintain open pastures that were also good for grazing game species. As grain and domesticated animals replaced these forest-gathering systems, orchards, hedgerow and silvopastures were adopted. In some cases, hazel was coppiced under oak standards. And throughout Europe, but especially in Spain, pigs were enlisted in converting acorns into pork.[3]

All along the California Coast Indigenous peoples forged abiding relationships to oaks. Half a dozen oak species were managed with fire to provide a staple starch to their diverse diets. In her book Tending the Wild M. Kat Anderson writes about the sophistication of Indigenous food systems management, which, in addition to fire included intentional cultivation and planting, pruning, weeding and training branches into particular shapes such as digging sticks, tools and arrows. The West Coast of North America’s balanocultures were some of the last peoples to rely so heavily on acorns as a staple food, though acorns are still widely consumed in parts of Asia, especially Korea.

In Octavia Butler’s novel The Parable of the Sower, the main character Lauren Oya Olamina, lives in a post-prosperity United States that is struggling to stay out of all out survivalist chaos. Her small community gardens and has returned to making bread from acorn flour. They represent a kind of post-apocalyptic balanoculture. Later, forced to leave her relatively secure neighborhood she forms a new religious movement called Earthseed and the community Laura forms with a rag tag group of survivors is named Acorn.

The Oak is an abundant gift giver. Gifts are a kind of language, oaks speak in seasonal flows of acorns, bark, truffles and leaves. The bark and leaves have traditionally been used as astringent and have anti-inflammatory properties that can stop bleeding or sooth external sores. It is also anti-diarrheal and antioxidant. The bark is also used for tanning and for wine making.

The wood is structurally very sound and sought after for fuel and fine woodworking such as ship building. Neolithic European dugout canoes were sometimes made of oak trees. The Lurgan canoe, was used over 4,000 years ago in Galway, Ireland. It was re-discovered in the early 20th century and measured more than fourteen meters long. In Medieval Europe, trees were trained to become specific parts of the ships’ hulls and body.

Image Source: http://irisharchaeology.ie/2014/10/the-lurgan-canoe-an-early-bronze-age-boat-from-galway/

Strong mature oak beams were also sought out to build the roofs of Westminster Abbey and Notre Dame. As an aside, when Notre Dame burned down in 2019, the restoration of the building insisted on using mature oak, which were sought from all over France. The Villefermoy forest has provided over 50 trees for the project. This was of course a controversial move, as more than 40,000 people signed petitions calling the cutting of oaks “ecocide.”

This foundational abundant gift giving on the part of oaks and their associated species, also contributed to the spiritual ecology that populated the imaginal realms of these primal peoples. For example, oak is a totem of almost all the sky gods within early Indo-European religious expressions. This probably means that oak was a sacred tree that later became anthropomorphized as the familiar male sky gods of Zeus/Jupiter, Dagda, Perun, Thor and Indra. These lightning bolt wielding thunderers were present in the form of oak, which itself has an affinity with lightning strikes due to its high water content. Even early fragments referring to Yahweh connect him to groves of trees some of which were identified as oaks. Later, extreme monotheists would cut down these sacred groves, so the official theology of Judaism’s relationship to trees certainly evolved. But after people, trees are the most often referred to entity in the Hebrew/Christian Bible.

In the Finnish epic The Kalevala, during the creation of the world, a massive oak tree shaded out the other trees, and more importantly the barley fields, from the sun.

“Spread the oak-tree’s many branches,

Rounds itself a broad corona,

Raises it above the storm-clouds;

Far it stretches out its branches,

Stops the white-clouds in their courses,

With its branches hides the sunlight,

With its many leaves, the moonbeams,

And the starlight dies in heaven.” (Rune II)

The tale’s hero Vainamoinen called on the goddess of Nature to help him. From the primal waters emerged a small man clothed in bronze. Despite his size, and tiny ax, he felled the mighty oak with three blows and Vainamoinen and his helper are again able to sow the fields and forests with seed. On one level the story reveals the tension that surely arose between the early balanocultures and the ascendant granocultures. The massive tree was not a tree of life, but a hindrance to the open growing conditions needed for barley.

In the Greek religious imagination, a dryad is a tree nymph or tree spirit. But the word Drys (δρῦς) is just the word for “oak” in Greek. Dodona was originally a center of worship and divination of a mother goddess, Dione, related to other feminine figures such as Rhea, Gaia, Hera and Aphrodite. Divination was often undertaken by listening to the rustle of leaves or to the sound of windchimes hung from the branches of sacred oak trees. Augury, or bird divination, was also done from within these sacred groves. By the 1200s BCE, Dodona had been appropriated by the cult of Zeus. But even then, a sacred oak was identified with him and was later walled off by King Pyrrhus (~290 BCE) to protect it.

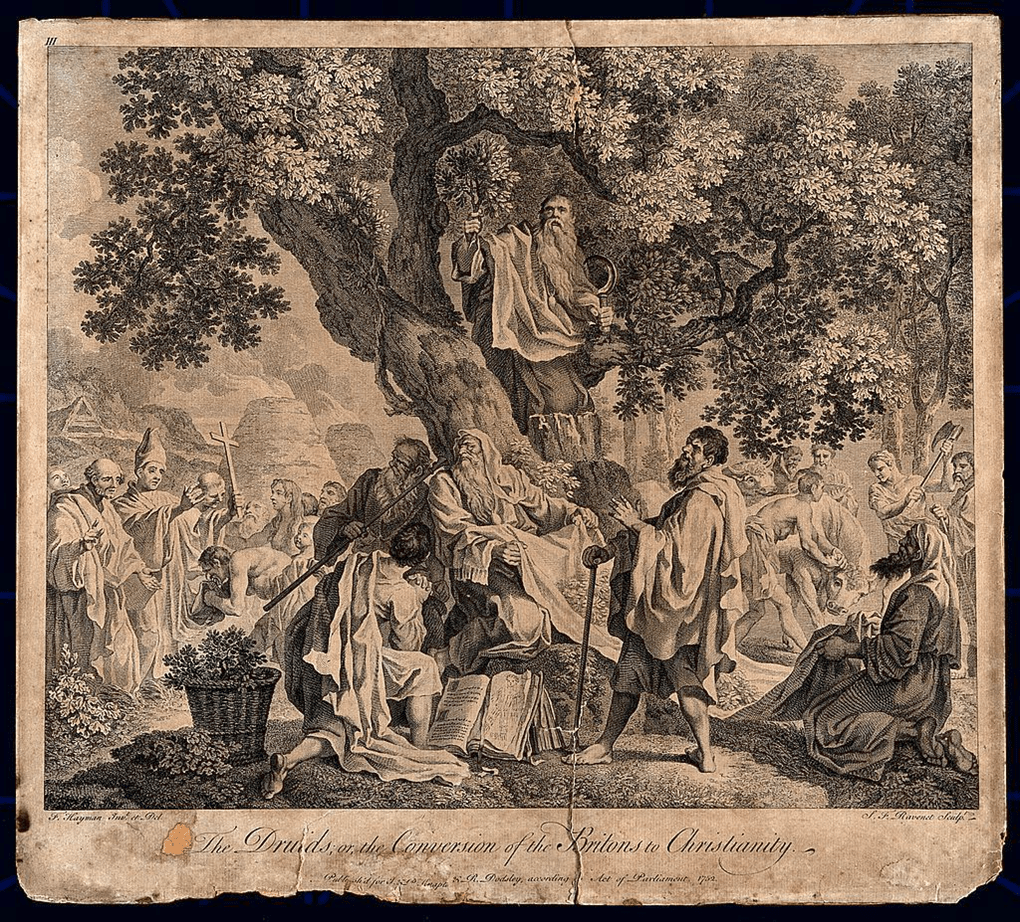

You have probably heard of the connection between oaks and Druids. In Ireland, the word Druid, the name for their scholar-priests, refers to groves of oak trees where they performed their councils, rituals and perhaps even human sacrifices. Druid is sometimes translated as “knower of oaks”, and the harvest of mistletoe from these oaks was a sacred rite. We don’t know much about them, and there is plenty of Neo-Pagan romanticism about their proto-ecological ethics, it is likely that human sacrifice was part of their oaken religious rituals. Nothing is certain about this however, because much of our information comes to us through Roman imperial eyes. What is certain, is that oaks played an important role in the foodways and spiritways of these pre-Christian earthy pagans.

The Garry Oak Reimagined

https://thefeelingoftheplace.com/portfolio_cat/garry-oaks/

In the Salish Sea Bioregion, Coast Salish territories, or Cascadia, where I live, we dwell alongside only a single oak species. The Saanich (SENĆOŦEN) word for this oak is ĆEṈ¸IȽĆ (pronounced chung-ae-th-ch). In botanical Latin, it is the Quercus Garryana—the Garry Oak (The same species I encountered in Oregon). The name Garry came from explorer David Douglas who named the oak for his friend Nicholas Garry of the Hudson’s Bay Company (1782–1852). The rest of this essay is about my dialogue with Quercus Garryana and trying to tune into what they may have to teach us about living together in this messy post-colonial world. For English speakers, I propose that we begin to call them the Cascadia Oak. Sorry Garry!

According to Western archeological pollen studies, the Cascadia Oak migrated here around 10,000 years ago and flourished at its greatest extent from 8000-6000 years before present. After that its range began to shrink as the climate grew wetter. Many histories of the Cascadia Oak in this region suggest that a Mediterranean climate “prevails” over most of the oak’s range. While the rain shadow of Vancouver Island certainly provides conditions more suitable for the Cascadia Oak, they seem to flourish best when humans co-manage their range with fire. If I understand my reading of the history correctly, the oak savannas and grasslands where the oaks are most iconic may have disappeared completely if it had not been for continuous Indigenous management. This entanglement with human culture is what fascinates and inspires me most about oak trees in general and the Cascadia Oak in particular. Oak savannas are not a rare ecosystem just because European colonialism has displaced or replaced them, they are rare because they need fire to maintain themselves. Left untended, Douglas fir trees overtop them, and unless a natural fire comes through, they likely will die out after a couple of decades.

The Cascadia Oak, like most oaks, are also social trees. Over 100 species of birds have been identified in Cascadia Oak woodlands. Hundreds of insects and invertebrates make their homes with Cascadia Oaks. Indigenous peoples up and down the west coast used their bark, leaves, wood and acorns as sustenance, medicine, and tools. Their ecologies were also hunting grounds and camas prairies (Camassia quamash), a flowering plant with a starchy tuber that was one of several root crops cultivated by Coast Salish peoples. The Capital of British Columbia, Victoria is originally named Camosun, or “place to gather camas.” Like California, Island and lower mainland British Columbia maintained strong balanocultural food systems.

Dialogue through Ecological Restoryation

In Anna Tsing’s book, The Mushroom at the End of the World, she shows us how another ecological dialogue has been going on for many thousands of years. She studies the ways that matsutake mushrooms have not just been prized gourmet foods, but how their allure has ebbed and flowed with human land management, especially second growth pine lands in Japan. She writes,

“…one could say that pines, matsutake, and humans all cultivate each other unintentionally. They make each other’s world-making projects possible…As sites for more-than-human dramas, landscapes are radical tools for decentering human hubris. Landscapes are not backdrops for historical action: they are themselves active. Watching landscapes in formation shows humans joining other living beings in shaping worlds.”[4]

In a similar way, the Cascadia Oak was an integral part of a diverse land-based food system that included clam gardens, berry patches, salmon and herring runs, hazel orchards and camas gardens. These food systems were intensively managed by Coast Salish and Vancouver Island First Peoples. Cascadia Oak savannas were kept open from encroaching fir forests using fire, even as the climate got wetter. Burning was a technique for enhancing a set of anthropocentric management goals: keep grasses vigorous, keep bugs out of the duff and acorns. European invaders did not recognize these landscapes as anthromes, or if they did, did not respect Indigenous tenure enough to care. Much of what was assumed to be wilderness or unclaimed, was in fact ancient active landscapes where humans and a myriad other species made each other’s “world-making projects” possible.

Fast forward to contemporary restoration ecology. In recent decades, the Pacific West of North America has seen several organizations pop up like mushrooms to protect and restore the Cascadia Oak’s unique and biodiverse ecology. It seems to me that the central dialogue or story of Restoration Ecology is one of repair, purification, and penance. Ecological experts restore species composition and ecosystem function to make right, restore balance, bring order back to the natural world, which Western humans, from the outside have disrupted. We are the serpent in the Garden. So, Cascadia Oak ecosystems are seen to be under threat from “invasive” species and development. The Garry Oak Ecosystem Recovery Team comes across like First Aid to a wounded ecological person. The medicine is to eradicate invasives, wall off ecological precincts and begin to implement professionally supervised prescribed burns to maintain oak prevalence over Douglas Fir.

This approach has its place, and endangered species must be given room to flourish. However, on their website, GOERT has a page dedicated to resources for gardeners and landowners. This is the approach that enchants me most. This is what I would call a Collaborative or Reconciliation Ecology. A more collaborative ecology might accompany us from a so-called “crisis narrative” in which wild nature is besieged by a voracious culture; to a “dynamic narrative” in which all cultures are understood in ever shifting relationships to biodiversity.

Wherein diverse biocultures and values collaborate in restoring plural relationships to places, species, foods and materials. Native and non-native species are welcomed (not necessarily invasives), and Indigenous and non-indigenous perspectives and technologies are experimented with. This Restoryation is about approaching ecosystems where humans are back in right relationship to places, not restricting them to the status of invader, visitor or tourist. If all we see when we look at changing ecosystems is loss, we are not seeing the possibilities that change might afford for fostering novel relationships that are regenerative.

The Indigenous peoples who stewarded Cascadia Oaks were not park rangers, they were managers, gardeners. So, what if we began to think of oaks, and many other species, not as victims to be saved and protected, but as interlocutors and companions in responding to the unfolding climate crisis. The plants that I know are going to fight like hell to keep on living. I want to fight alongside them, not as a savior but as collaborator and kin. I want to grieve losses as they happen, but I also want gardening, which is a kind of ecological dialogue, to become one of many tactics for resisting consumerism and climate doom.

Restoryation, is not so much about a re-consecrating and purifying an ecosystem of its human influence as an act of environmental penance, it is about restoring our relationship to the earth community, a relationship which has been betrayed in many ways throughout time by our rampant and destructive economic culture. Ecologist Stephanie Mills even suggests that restoration, Restoryation, is a form of ecological ritual:

“[The act of restoration] gives [people] a basis for commitment to the ecosystem. It is very real. People often say, we have to change the way everybody thinks. Well, my God, that’s hard work! How do you do that? A very powerful way to do that is by engaging people in experiences. It’s ritual we’re talking about. Restoration is an excellent occasion for the evolution of a new ritual tradition”.[5]

We don’t have to endure the coming losses and changes in isolation. We have each other and we have the living, breathing world on our side. Oaks, like so many of the species on this planet, are here to dialogue with us about how to live in a chaotic and changing world, and for me at least, that makes fighting for a just and livable world just a little bit less lonely.

Cascadia Oak Organizations

https://ohgarryoaksociety.org/

Resources

French Oaks

North American Ethnobotany search for Gambel Oak

http://naeb.brit.org/uses/search/?string=Quercus+gambelii

Garry Oak

http://naeb.brit.org/uses/search/?string=Quercus+garryana

Stories

https://www.madrona.org/news/coast-salish-stories

MacDougall et al. Defining Conservation Strategies with Historical Perspectives: a Case Study from a Degraded Oak Grassland Ecosystem https://conbio-onlinelibrary-wiley-com.proxy.lib.sfu.ca/doi/pdf/10.1111/j.1523-1739.2004.00483.x

[1] Robin Wall Kimmerer, ‘Speaking of Nature: Finding language that affirms our kinship with the natural world’ https://orionmagazine.org/article/speaking-of-nature/

[2] Suzanne Simard, Finding the Mother Tree: Discovering the Wisdom of the Forest (Allen Lane, 2021), 277.

[3] Max Paschall, “The Lost Forest Gardens of Europe” 2020, https://www.shelterwoodforestfarm.com/blog/the-lost-forest-gardens-of-europe

[4] Anna Tsing, The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins (Prinston University Press, 2015), 152.

[5] Stephanie Mills, In Service of the Wild: Restoring and Reinhabiting Damaged Land.

(Boston: Beacon Press, 1995), 125.