I am driving to Calgary to pick up my parents from the airport so we can tour Banff and Jasper National Parks. It is going to be Disneyland-dense with fellow tourists, each of us seeking to feel something like awe, to connect with the rawest aspects of nature. Still, I am very excited to go and see the beauty of the Canadian Rockies!

From Vancouver I decided to take the southern route along the US border which passes through the Kootenays on Highway 3. It was a stunning drive, even with the pangs of climate anxiety I occasionally nursed from seeing massive clear cuts, fire scarred mountainsides, aspen groves drying out too soon, and browned-over fir forests dying from some unknown pathogen (Spruce bud worm?).

While I was planning my trip, I realized that the route would take me right through the traditional heartland of the Doukhobors, an ethno-religious community originally from Russia. I learned about the Doukhobors shortly after moving to BC, when I was chatting with the barber cutting my hair (I had more then). I told her I was studying religion and ecology at UBC, and she told me she grew up in a Doukhobor village in the Kootenays.

As I came to learn, the Doukhobors emerged in the late 1600 and early 1700s. The word means “Spirit Wrestlers”, and as a sect of radical Christianity, they were known for their communalism and simplicity. Some of their beliefs are similar to branches of Radical Reformation groups such as the Amish and the Mennonites. The Doukhobors however also resemble the Quakers in that they believed that God dwells in every person, and that this meant clergy and even scriptures were not necessary. Instead, they speak of the “Book of Life”, wisdom embodied in sayings, hymns, psalms and prayers.

If this was not controversial enough, they got into more hot water in 1734 when they were declared iconoclasts for preaching against the use of icons, a cherished piety in the Russian Orthodox Church. Eventually they came to espouse a vegetarian diet for ethical rather than ascetical reasons and as pacifists, they refused to swear oaths or join the military.

They were persecuted by Russian Orthodox clergy and a string of Tzars. Many were forced to migrate to various places in the Transcaucasia region and their leaders were often exiled to Siberia. In 1895, a group of Doukhobors burned their weapons in protest, causing another wave of persecution. One community attempted to settle in British controlled Cyprus, but soon many died of disease in route.

In 1899, around 6,000 Doukhobors emigrated to Saskatchewan with the help of local Quakers and Russian pacifist author Leo Tolstoy. Others such as Russian anarchist Peter Kropotkin and professor of economics James Mavor at the University of Toronto donated to the cause. By 1930 there were over 8,000.

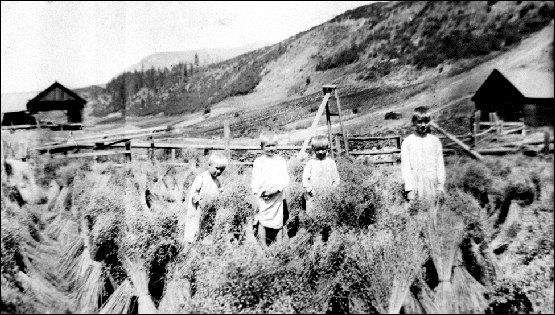

They worked on communal farms and ran a grain mill and a brick factory among other things. They built communal dormitories, but unlike the Shakers of New England, they were not celibate. Their communal land and pacifism eventually got them in trouble with the Canadian government as well. In 1906, they refused to surrender their communal title to land and lost much of it to the Crown when a law was passed requiring landownership to be under a single person’s name. During the world wars, they were also resented by Canadians for not supporting the war effort. In the 1920s, a breakaway group calling themselves the Sons of Freedom staged naked protests and engaged in arson attacks against more law-abiding Doukhobor families causing tensions within the community.

Today, the majority of practicing Doukhobors live in Grand Forks and other areas of British Columbia. Many moved here in 1908 after the Canadian law against communal landholding. Tensions also grew within the community, and it seems likely that a Doukhobor bombed the train that community leader Peter V. Verigin (1859-1924) was on as he headed to British Columbia in 1924. So much for pacifism (though we still don’t know who planted the bomb). Some of the Doukhobor children were forcibly interned into boarding school much like Indigenous residential schools.

I pulled up to the Doukhobor meeting house, now officially called The Union of Spiritual Communities of Christ (USCC) and noticed several veiled women making their way to the door accompanied by men and some younger folks. A large stylized dove adorned the doorway, symbolizing the Holy Spirit, and their persistent commitment to peace.

I had planned to just snap a picture and be on my way, but when I realized that they were gathering for service, it was Sunday after all, and I happened to arrive at the top of the hour, it seemed providential that I attend the meeting. I guess I half expected them to speak only Russian, but when I wandered over and asked a young man if the public were allowed to attend, he spoke to me in unaccented English and said, “of course!” I was greeted warmly by all and began chatting with one of the men, who immediately inquired as to my own religious convictions. I told him it was a long, meandering story, but that I had been raised in the Mormon tradition. I mentioned that in my view, Mormons shared a few similarities—a health code (The Word of Wisdom), early experiments with communalism (The United Order), friendly people, and a love for the land they settled in Utah.

There were about a dozen and a half people attending the service, with men and women sitting on opposite sides facing each other. There was a small table at the front that held a loaf of bread, a pitcher of water and a small wooden bowl of salt. These symbols, which we never partook of during the service, were symbolic of “hospitality, sharing, and our basic principle—Toil and Peaceful Life.” (from the Doukhobor hymn book).

The service was simple, the singing beautiful. They did a sort of ritual greeting call and response as people entered. The women were veiled and the elder women dressed in what seemed like more traditional dress, though I saw one carrying her things in a Lululemon bag. They sang and prayed in Russian and bowed after each hymn. There was also a sort of passing of the peace ritual during the beginning which involved three handshakes and a kiss. But only a few folks in the first rows did it. Toward the end they asked me to come to the front and say a few words, and I introduced myself and thanked them for their hospitality, kindness and way of life. After the service I perused some of the historic wall photos, chatted a bit more and was given a stack of literature to take with me.

The experience left me feeling a mix of familiar longing and a bit of sadness. And I am not quite sure how to articulate it… perhaps a part two of this essay is in order, or perhaps not.