In Part I, I wrote about my visit to a small religious community called the Doukhobors. Those who remain of this fascinating religious movement live mostly in the Kootenays region of British Columbia. I enjoyed visiting the Doukhobor service and getting to know a few of them. But I left feeling a mix of peace, sadness and a familiar longing. In this short piece, I want to put words to these emotions, even if just to work through them for myself.

I have always felt that there is something beautiful about group religious worship and identity. There is such a strong sense that those in the room know who they are, where they are, and why they are. I still appreciate this when I attend a religious service, visit temples, monasteries, or gurdwaras. I even appreciate this when I return to a Mormon meetinghouse with my family during the holidays. Though I have long since stopped identifying and practicing the religion of my upbringing, the familiar hymns, the inflection of prayer, the smell of a church, and everyone dressed in their Sunday best, tap into my longing for be-longing.

The sadness is harder to articulate. I think is has to do with a mixture of spiritual and existential loneliness. Though the Mormon / LDS tradition never espoused as radical an approach to Christianity as the Doukhobors, like many restorationist movements in the 19th century, they were certainly committed to living out Christianity in what they saw as an authentic and radical way. And I would even say that Mormonism’s roots were what led me to my exploration of radical politics.

At the Mormon university I attended, I really struggled with how overwhelmingly partisan Mormon culture can be, especially in the so-called Book of Mormon belt. By that I mean intentionally aligning itself with the US Republican Party. As if Jesus or Joseph Smith were teaching modern conservative talking points. I had always seen religion differently, and I soon found a community of more left-learning and radical Mormons, many soon to be ex-Mormons, and I felt very seen and understood in my leanings and struggles.

As I wrestled and read, I sympathized with more radical formulations of Christianity by authors like Leo Tolstoy, and non-religious writers Peter Kropotkin and Murray Bookchin. I even wrote an article about the first convert to Mormonism in Mexico, the Greek radical Plotino Constantino Rhodakanaty (1828-1890). Like him I saw something powerful at the heart of the early Mormon relationship to land, place and social organization. The Mormons attempted to create The United Order as a cooperative social-economic system. It was never fully realized. Like Rhodakanaty, I was eventually disillusioned with Mormonism’s assimilation of the American capitalist religion, though I tried for years to find my own sort of Mormon radicalism. I wrote several articles for a Catholic Worker inspired newspaper called The Mormon Worker. That was a long time ago.

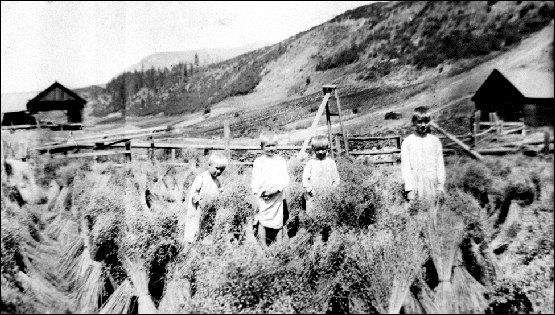

I also felt sad because the Doukhobors are dwindling, and their tradition cannot live as they envisioned. As I chatted with my new Doukhobor friends, they related to me how the community gets along today, and how it has had to adapt with the times, and how from their peak in the early 20th century, only about 1,675 identify Doukhobor as their religion, according to the 2021 Canadian census. The Doukhobors work through a legal nonprofit structure, they do not own land communally, and many don’t bother observing vegetarianism anymore. I understand, but in addition to the existential loneliness of longing for belonging, seeing a tradition with such a beautiful way of live dwindling is a bit tragic.

And it’s not as though I would want to be Mormon again or become a Doukhobor, even if they were more radical. But there is a nameless love that is hidden inside the feeling I got sitting with the Doukhobors and listening to them sing together. After the visit, back on the road, I was marketed to by countless fruit stands, new distilleries, luxury retreats and resorts and excursions. The warm summer world seemed to be buckling under the weight of us ravenous experience-seeking tourists. This is a landscape of leisure, of make believe, of Air BnB rentals, cabins and resorts for the religion of consumerism. It feels like the opposite of that nameless longing. It feels like the contours of a spiritual wasteland of sorts. Always seeking, never finding, we wander around hungry for meaning and experiences. Why is this “religion” flourishing while the Doukhobors languish? I don’t know. But I want to keep finding places where I feel that feeling and keep trying to name that nameless love that is hiding within it.