[Homily delivered Feb. 26, 2017 to Saint Margaret Cedar-Cottage Anglican Church.]

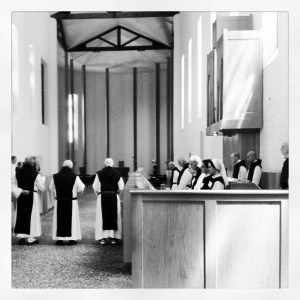

At 4:13 AM I stumbled in the pale darkness to my choir stall. When I finally looked up through the west facing window of the chapel at Our Lady of Guadalupe Abbey in northwestern Oregon, a glowing full moon was setting through a light haze. The monks began to chant the early morning Divine Office of Vigils, a ritual that unfolds day after day, month after month, and year after year in monasteries all over the world.

This month-long immersive retreat in 2014, inspired the questions that would become my PhD dissertation research, which I completed over a six month period in 2015 and 2016. I am now in writing the dissertation, and should be done in the next 2, 3, 4 or 5 months. I wanted to better understand the relationship between the 1,500 year old monastic tradition, contemporary environmental discourses and the land. And I wanted to better describe for the emerging Spiritual Ecology literature the ways that theological ideas and spiritual symbols populate monastic spirituality of place and creation.

In the readings this morning, we are gifted several land-based symbols. God says to Moses in Exodus: “Come up to me on the mountain.” Liberated from Egypt, God is now eager to build a relationship with his people and Moses’s ascent of Mount Sinai to receive the Law mirrors our own spiritual journeys. A thick cloud covered the mountain for six days before Moses was finally called into God’s presence, like so much of my own spiritual life, lived in darkness, with small rays of light.

In the Gospel reading, Jesus too ascends a “high mountain.” There, his disciples witness one of the most perplexing scenes in the New Testament: The Transfiguration. Jesus’s face and garments shone like the sun. And then, certainly conscious of the Hebrew text, the writer says that a bright cloud overshadowed them and they heard a voice say: “This is my Son, the Beloved; with him I am well pleased; listen to him!” Christ, who was fully human and fully God, was revealing in his very person to Peter, James and John his fulfillment of the Law and the Prophets. And presence of the symbols of mountain and cloud were bound up in the authenticity of Jesus’s claims to messianic authority.

Even though it’s not clear that the Apostle Peter is the author of our second reading, the message is clear: “For we did not follow cleverly devised myths when we made known to you the power and coming of our Lord Jesus Christ, but we had been eyewitnesses of his majesty.” Reading Exodus and Matthew, it might feel simple to slip into an easy allegorical hermeneutic, to see everything as a symbol; but the writer of 2 Peter is clear: Stop trying to turn everything into a myth! This reminds me of the quote from Catholic writer Flannery O’Conner who said of the Real Presence in the Eucharist, “If it’s just a symbol, to hell with it.”

With these texts in mind, especially questions of religious symbols and religious realities, I want to talk a little bit about my research with monastic communities, and then return to these texts at the end. Monasticism, like Christianity as a whole is steeped in symbols. For example, the Abbas and Ammas of the early monastic tradition experienced the desert as a symbol of purification and sanctification. Saint Anthony fled to the desert to live a life of solitude, spiritual warfare and strict asceticism. The silence and nakedness of the desert landscape was as it were a habitat for the silence and simplicity that led the Desert Fathers and Mothers through the wilderness of their own sin to the simplicity of God’s presence. As Saint Jerome wrote, “The desert loves to strip bare.”

With these texts in mind, especially questions of religious symbols and religious realities, I want to talk a little bit about my research with monastic communities, and then return to these texts at the end. Monasticism, like Christianity as a whole is steeped in symbols. For example, the Abbas and Ammas of the early monastic tradition experienced the desert as a symbol of purification and sanctification. Saint Anthony fled to the desert to live a life of solitude, spiritual warfare and strict asceticism. The silence and nakedness of the desert landscape was as it were a habitat for the silence and simplicity that led the Desert Fathers and Mothers through the wilderness of their own sin to the simplicity of God’s presence. As Saint Jerome wrote, “The desert loves to strip bare.”

The motifs of the Desert-wilderness and the Paradise-garden are like two poles in Biblical land-based motifs. Pulling the people of Israel between them. Adam and Eve were created in a garden, but driven to the wilderness. The people of Israel were enslaved in the lush Nile Delta, but liberated into a harsh desert. The prophets promised the return of the garden if Israel would flee the wilderness of their idolatry. Christ suffered and resurrected in a garden after spending 40 days in the wilderness. The cloister garden at the center of the medieval monastery embodied also this eschatological liminality between earth and heaven, wilderness and garden.

Mountains too were and continue to be powerful symbols of the spiritual life. From Mount Sinai to Mount Tabor, John of the Cross and the writer of the Cloud of Unknowing, each drawing on the metaphors of ascent and obscurity.

But do you need a desert to practice desert spirituality?

Do you need the fecundity of a spring time garden to understand the resurrection?

I would argue that we do.

For my PhD research, I conducted 50 interviews, some seated and some walking, with monks at four monasteries in the American West. My first stop was to New Camaldoli Hermitage in Big Sur, California. The community was established in 1958 by monks from Italy. The Hermitage is located on 880 acres in the Ventana Wilderness of the Santa Lucia Mountains. Coastal Live Oak dominate the erosive, fire adapted chaparral ecology, and the narrow steep canyons shelter the southernmost reaches of Coastal Redwood. The monks make their living by hosting retreatants and run a small fruitcake and granola business.

The second monastery I visited was New Clairvaux Trappist Abbey, which is located on 600 acres of prime farmland in California’s Central Valley and was founded in 1955. It is located in orchard country, and they grow walnuts and prunes, and recently started a vineyard. They are flanked on one side by Deer Creek, and enjoy a lush tree covered cloister that is shared with flocks of turkey vultures and wild turkeys that are more abundant than the monks themselves. They recently restored a 12th century Cistercian Chapter house as part of an attempt to draw more pilgrims to the site.

Thirdly, I stayed at Our Lady of Guadalupe Trappist Abbey, which was also founded in 1955, in the foothills of the Coastal Range in Western Oregon. When they arrived, they found that the previous owner had clear cut the property and run. They replanted, and today the 1,300 acre property is covered by Douglas fir forests, mostly planted by the monks. Though they began as grain and sheep farmers, today the monastery makes its living through a wine storage warehouse, a bookbindery, a fruitcake business, and a sustainable forestry operation.

For my last stop, I headed to the high pinyon-juniper deserts of New Mexico. At the end of a 13 mile muddy dirt road, surrounded by the Chama River Wilderness, an adobe chapel stands in humble relief against steep painted cliffs. Founded in 1964, Christ in the Desert Abbey is the fastest growing in the Order, with over 40 monks in various stages of formation. The monks primarily live from their bookstore and hospitality, but also grow commercial hops which they sell to homebrewers.

In my interviews, the monastic values of Silence, Solitude and Beauty were consistently described as being upheld and populated by the land. The land was not just a setting for a way of life, but elements which participated in the spiritual practices of contemplative life. To use a monastic term, the land incarnates, gives flesh, to their prayer life.

Thus, the monks live in a world that is steeped in religious symbols through their daily practice of lectio divina, and the chanting of the Psalms. As one monk of Christ in the Desert put it:

“Any monk who has spent his life chanting the Divine Office cannot have any experience and not have it reflect, or give utterance in the Psalmody. The psalmody is a great template to place on the world for understanding it, and its language becomes your own.”

In this mode, the land becomes rich with symbol: a tree growing out of a rock teaches perseverance, a distant train whistle reminds one to pray, a little flower recalls Saint Therese of Lisieux, a swaying Douglas fir tree points to the wood of the cross, a gash in a tree symbolizes Christ’s wounds. In each case, the elements of the land act as symbol within a system of religious symbology. One monk of Christ in the Desert, who wore a cowboy hat most of the time related:

“When the moon rises over that mesa and you see this glowing light halo. It echoes what I read in the Psalms. In the Jewish tradition the Passover takes place at the full moon, their agricultural feasts are linked to the lunar calendar. When they sing their praises, ‘like the sunlight on the top of the temple,’ ‘like the moon at the Passover Feast.’ ‘Like the rising of incense at evening prayer.’ They’re all describing unbelievable beauty. I look up and I’m like that’s what they were talking about.”

The land populates familiar Psalms, scriptures and stories with its elements and thus enriches the monastic experience of both text and land.

Theologically speaking, God’s presence in the land is a kind of real presence that does not just point to, but participates in God. This gives an embodied or in their words, incarnational, quality to their experience of the land. As another example, one monk went for a long walk on a spring day, but a sudden snow storm picked up and he almost lost his way. He related that from then on Psalm 111 that states “Fear of the Lord is the beginning of wisdom” took on a whole new meaning.

In addition, the monks often spoke of their experiences on the land in terms of flashes of insight, or moments of clarity that transcended any specific location or symbolic meaning. One monk called these experiences “charged moments” where a tree or vista one sees frequently, suddenly awakens to God’s presence.

The monks at each community, in their own ways, have sunken deep roots into the lands they live on and care for. Each, in the Benedictine tradition, strive to be “Lovers of the place” as the Trappist adage goes. When I asked one monk if this meant that the landscape was sacred, he paused and said, “I would only say that it is loved.”

I am arguing in my dissertation that monastic perception of landscape can be characterized as what an embodied semiotics. By this I simply mean that symbols and embodied experience reinforce each other in the landscape, and without embodied experience symbols are in danger of losing their meaning.

The motifs of desert and wilderness, the symbols of water, cloud, mountain, doves, bread and wine, the agricultural allegories of Jesus, and the garden, are in this reading, reinforced by consistent contact with these elements and activities in real life.

On the last Sunday before Lent, as we move into the pinnacle of the Christian calendar, it is no coincidence that the resurrection of the body of Jesus is celebrated during the resurrection of the body of the earth. But does this mean that Jesus’s resurrection can be read as just a symbol, an archetype, a metaphor for the undefeated message of Jesus? Certainly Peter and the other Apostles would say no. They did not give up their own lives as martyrs for a metaphor.

For a long time I struggled with believing in the resurrection as a historical reality. But when I began to realize the connection between the land and the paschal mystery, it was the symbols in the land itself that drew me to the possibility of Christ’s resurrection. And that in turn reinforced my ability to see Christ in the entire cosmic reality of death and rebirth active and continual in every part of the universe.

As Peter warns his readers: “You will do well to be attentive to this as to a lamp shining in a dark place, until the day dawns and the morning star rises in your hearts.” For how can we truly believe in the return of the Beloved Son, if we have never been up early enough to see the return of the star we call sun?

![IMG_3027[1]](https://holyscapes.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/img_30271.jpg?w=300)