My local grocer decided to display severed Buddha heads and Tostitos. Why not?

My local grocer decided to display severed Buddha heads and Tostitos. Why not?

Saint James Anglican Church

I attend a High Mass Anglo-Catholic Parish in Vancouver called Saint James. There are sometimes 12 people in the Chancel at a time, attending to the consecration of the Eucharist, swarming in dervish like semi-circles around the eastward facing priest. Priests, deacons, sub-deacons, acolytes, thurifer, torch bearers and crucifer. No single one of us, even the priest makes the dance complete. We are each an integral part of the liturgical ecology.

This is of course not a food chain, but food is involved. Our oikos is the altar, the place where we bring the fruits of the land, the work of human hands, and ourselves, and to turn it, ever so slowly, into God. As an ecosystem transfers energy from up the trophic hierarchy from simple to complex organisms, so we during the liturgy, move the desires of our hearts into God’s desires; a little more each day.

It is true, that if we stay on the surface, the liturgy can be boring and repetitive. But just under the surface, the intricate dance that turns bread and wine into the body and blood of Christ on the altar, is an icon for the everyday intricacy that turns our food into our bodies; bodies that make up the mystical body of Christ.

In the spring,

The pale yellow-green leaves of the maples

Bleed into the rich yellow plumage of the just-arrived warblers.

By the time the maple leaves are deep green with summer,

The warblers will have gone.

–May 17, 2017

Standing on the creaky porch of Park Butte fire lookout, it felt like I was face to face with the southern slope of Mount Baker. Thirty miles east of Bellingham, Washington, on this 4th of July, the trail had been practically empty. I stayed the night in the lookout, and watched the colorful flicker of fireworks on the coast below mirror the twinkle of the stars above. As I began my hike down the next morning, I wanted somehow to reverence the commanding presence of the mountain in whose close proximity I had slept. I asked myself a simple question: Does it matter if I think of the mountain by its Settler name? Or, should I refer to it by its Lummi name: Kulshan?

I didn’t really know anything Mr. Baker, except that he was English; or much about the word Kulshan, except that it was one of the hip new breweries in town. So, I mustered a hasty sign of the cross, brought my hands close to my heart, and said ‘thank you.’

After my trip, I began to do a little research. Mount Baker is a 10,700 foot, relatively young at 100,000 years, active strato-volcano. Which means it is made up by layers of igneous rock, lava and pumice. It is glaciated, and snow-covered year round and has one of the highest snowfalls in the world.

Coast Salish peoples have dwelt in the area for at least 14,000 years. The Lummi word for the peak is as I already knew Kulshan, but it doesn’t mean White Sentinel, or The Shining One as I had heard. The word means something closer to ‘puncture wound.’ For the nearby Nooksack people, Kulshan actually refers to the area around the peak, used for hunting and gathering. Kweq’ Smánit, which simply means ‘white mountain’, is the name for the summit.

There are at least two stories associated with Kulshan. A 1919 ethnography recorded a retelling of the story of the Thunderbird, a supernatural being who dwells in the tops of mountains. A Lummi man related

“Thunder is caused by a great bird…the thunderbird is many hundreds of times larger than a fish hawk. It is so large that it can carry a large whale in its talons from the ocean to its nest….This huge bird has its home yonder on Mt. Baker, where you see the clouds piling up now. Whenever this bird comes from its nest and flies about the mountain top it thunders and lightnings, and even when it is disturbed in its nest it makes the thunder noise by its moving about even there…. The lightning is caused by the quick opening and shutting of its powerfully bright, snappy eyes and the thunder noise by the rapid flapping of its monstrous wings” (Reagan, 1919, 435).

The Thunderbird is a being in most if not all Coast Salish cosmologies, and it is often both a respected and feared presence in the land that demands respect and sometimes placation through the burning of ceremonial fires. For the Squamish peoples, the rich deposits of obsidian are places where lighting that shoots from thunderbirds eyes hit the earth.

The ethnographer Charles Buchanan in 1916, recorded another story of a man named Kulshan who had two wives; one beautiful, and one kind. Kulshan loved the kinder wife more, and the beautiful wife grew jealous and decided to leave him, hoping he would realize what he lost and come after her. As she walked south, she turned back many times to see if Kulshan was looking, and as she got farther away she had to stretch higher and higher to see Kulshan. Eventually she made camp on a high outcropping and stared back at Kulshan, waiting for him to come. Eventually she turned into the peak we today call Mount Rainier, and he into Mount Kulshan.

During the age of conquest, the mountain was sketched by Gonzalo Lopez de Haro on a Spanish voyage in 1790. He named it ‘La Gran Montaña de Carmelo,’ in reference to both Mount Carmel, but also the Carmelite Order, home of Saint John of the Cross and Teresa of Avila. In 1792, it donned the now familiar name of Englishman Joseph Baker, who was Captain George Vancouver’s Lieutenant.

Over the years, Anglo mountain climbers, ethnographers and history buffs have been in favor of renaming the peak Kulshan. Proof of this are the dozens of local businesses, mountaineering clubs, or botany societies who have taken it on as a namesake. But in doing so are we paying deference to an authentic place-name tradition? Or feeding our own ideas about indigeneity? Perhaps both.

Personal Spiritual Ecology

Acknowledging indigenous place-names certainly look toward a reconciliatory stance, provided it is accompanied by respect for sacred sites, more resource management autonomy, and Treaty and Title rights if possible. However, phenomenologically, a place-name does not automatically give us admittance to the world the name upholds. For example, Coast Salish place-names are fairly simple descriptives: ‘white mountain’, ‘place for herring fish’, etc. It is rather, the activities of dwelling that accumulate around those place-names that give rise to an experience of the world. This is beautifully illustrated of course by Keith Basso’s Wisdom Sits in Places but unlike Basso’s semiotic approach, Tim Ingold’s insights show us that landscape is not just a cultural layer we project onto the physical world, but the world itself. While I might be able to understand or recall certain Coast Salish place-names or stories, I must admit that I do not dwell in that world, and an attempt to do so for my own academic or spiritual curiosity carries with it the weight and suspicion of the colonialism of the last 200 years. In addition, in retelling these stories, there is the danger not only of losing details in translation, but importing my own world into the telling. And yet, are there any ontologies, especially today, that are not plural? Hybrid?

Learning about the history of the mountain, I confess that Mount Carmel resonated most with me. I am of course aware that to stick with ‘Carmel’, is to return to where we started, to run the risk of perpetuating imperial Christianity; but it is also to connect the place to the rich contemplative spiritual tradition of which I am a practitioner. John of the Cross’s Ascent of Mount Carmel, features the mountain as a symbol for our longing for union with God.

Lastly, regardless of one’s spiritual orientation, the land can speak to us in ways that we cannot always predict. I recall sitting in a discussion group at a Salish Sea conference. I made some point about place names. A Nooksack woman responded patiently that it was not we who named places, but the places themselves that gave people their names as gifts when they are ready. Translated into contemplative spirituality, this is the practice of attention, or, Prosoche (pro-soh-KHAY) in Greek. Being present a person, place, or organism, we listen to what they might say about the world, about ourselves, or about God. Perhaps it is with this practice that new names and thus, new worlds might arise.

This paper was presented at the recent Mountains and Sacred Landscapes Conference at the New School for Social Research in New York City.

References

In today’s Gospel reading from John 20:12-15 we read:

“But Mary stayed outside the tomb weeping. And as she wept, she bent over into the tomb and saw two angels in white sitting there, one at the head and one at the feet where the body of Jesus had been. And they said to her, “Woman, why are you weeping?” She said to them, “They have taken my Lord, and I don’t know where they laid him.” When she had said this, she turned around and saw Jesus there, but did not know it was Jesus. Jesus said to her, “Woman, why are you weeping? Whom are you looking for?” She thought it was the gardener and said to him, “Sir, if you carried him away, tell me where you laid him, and I will take him.”

We all know what happens next. This familiar Easter narrative has both delighted and puzzled Christians over the centuries. Mary Magdalene, a woman, was the first to see the resurrected Jesus. She was the Apostle to the Apostles, the first member of the Christian Church. We have often wondered, however, why it was that she did not immediately recognize Jesus.

One Jewish legend of the time, attempting to discredit the story of the resurrection, speaks of a man named Judas, who was worried that Jesus’s disciples would trample his cabbages when they came to visit his tomb. So, he relocated Jesus to another tomb, and the myth of the resurrection began. It is said by Biblical scholar Rudolf Schnackenberg, that perhaps this story is the reason John’s Gospel refers to Jesus as a gardener in the first place.

Other commentators have of course pointed to Mary’s grief, or even her focus on the worldly body of Jesus as reasons why she did not at first see her Teacher. Or, perhaps the author of the Gospel was playing with the familiar ancient trope of the disguised returning hero (See Homer’s Odyssey).

I would like to suggest a much simpler possibility. Perhaps Mary mistook Jesus for a gardener, because he was gardening. The scripture says that Mary turns around and sees Jesus there, it does not say that Jesus was facing her. Perhaps she noticed his presence, but his face was obscured because he was hunched over, hands in the dirt, taking in the smells of the earth on the early morning after he had suffered so much, and been miraculously returned to life.

The dialogue that ensues between Mary and Jesus could have taken place at a short distance, as Jesus playfully repeats the words of the angels, “why are you crying?” and Mary hopelessly asks if perhaps he knows where her Teacher has been laid. Perhaps he then got up from his task, and put his hand on Mary’s shuddering shoulder and spoke more directly: “Mary!” And when she looked up, only then did she recognize the face of the man she had come to love and respect so much.

Now, of course this is speculation, but I feel like this reading enriches many of the existing elements of symbolism in salvation history. As many commentators have pointed out from the earliest days of the church, including Paul, whereas Adam brings sin and death into the world through disobedience in the Garden of Eden, it is Christ, who in the Garden of Gethsemane and then the garden of the tomb points to the final Garden of the Resurrection. The Garden of Eden begins the salvation narrative, and the garden tomb finishes it. Jesus is the new Adam, as Mary is the new Eve. Christ suffered in a garden. He rises in a garden. As the second Adam, he is the “Greater Gardener.”

Sometimes we imagine the resurrected Jesus as a white-clad, angel like man. But the accounts of the resurrection, often portray him in day-to-day scenes. He appears to Apostles in a small room, and eats with them; He appears to two men walking along the road, and again eats with them; He sits by the Lake of Galilee and cooks breakfast over a fire. I am reminded of the familiar Zen Koan, “Before enlightenment, chop wood, carry water. After enlightenment, chop wood, carry water.” Before the resurrection, fully human and fully divine, after the resurrection, fully human and fully divine.

We will never know for certain of course, but there is nothing that convicts me of the both the reality and naturalness of the resurrection more than watching the cycles of birth, life, death, decay and rebirth that happen each year in the garden that we call earth.

References

Schnackenberg, Rudolf. The Gospel According to St. John: Volume III. Crossroad, 1990.

About a week before Lent began, I took a retreat to a Benedictine monastery in central Washington. Unlike several of the other monasteries I have visited, this particular monastery was located in a more suburban setting, and, founded as a small college, the monastery is now a bustling university.

I went hoping for some silence, writing time and immersion in the familiar rhythms of the monastic liturgy. When I arrived, however, the first thing I noticed when I got out of the car, was how loud it was. I could hear I-5 rushing and hushing in the background. In addition, the liturgy was not chanted but spoken, which made it feel less vibrant, and the space of the chapel was one of those ill conceived modernist boxes. Nonetheless, the monks were kind, and I enjoyed talking with them, and learning about the monastery’s history.

The monastery started with close to 600 acres, but now retained only about 350, most of which was devoted to the campus and student housing. They had a small farm operation in the 1930s-1950s but it ended by the 1960s. Even with a smaller footprint, the monastery had taken good care of the remaining second or third growth forests, which had a number of walking trails. And even with the white noise of the freeway in the background, I enjoyed walking them.

Despite the loveliness of the forest, I ended up having a difficult time writing, felt restless during the spoken Divine Office, and everywhere I went, the freeway was audible. I ended up leaving early, so I could get home and regroup.

On the way, feeling the weight of dissertation anxiety and something of the distance that opens between us and the Divine at times, I decided to go for a hike at my favorite protected area in Bellingham, Washington, Stimpson Family Nature Preserve. It was late in the afternoon, and a friend and I headed around the wet, still snowy in places, trail.

It is one of the few older growth forests in the area, and I often feel God’s presence there as I breathe the clean cool air, and marvel at the riot of colors. But this time, riding the wave of restlessness from my retreat, I felt a very strong sense of God’s absence. It hit me like a wave, a sudden pang of nihilistic agnosticism, and the darkening forest, still silent and deadened to winter, felt cold, indifferent and lifeless.

For several days after this, I pondered the dark mood that had descended. I stopped praying, and considered skipping Church for a few weeks. My usual excitement for Lent turned into a smoldering dread.

I recently decided to join an Anglo-Catholic Parish in Vancouver because of its wonderful liturgy, and I had signed up to be part of the altar party as a torch bearer on Ash Wednesday. So, despite the darkness that had descended onto my spiritual life, I decided to go.

At first I felt sad, and distant, but as the liturgy proceeded, my attention sharpened, and I began to feel lighter. During the consecration of the Eucharist, which like Traditionalist Catholic Mass is said with the Priest facing the altar, as torch bearer, I knelt with the candle behind the priest. As the bells rang and the priest lifted the bread and then the wine, a subtle shift occurred in my chest. The utter strangeness and beauty of the liturgy penetrated my dark mood, and lifted me back into a place of openness and receptivity. It was nothing profound, or revelatory, but a perceptible change. I was again, ready to enter into simplicity and silence of Lent, in anticipation of Easter.

Reflecting on this ‘Dark Night of the Soul’, I began to understand the gift that God’s absence can sometimes be. I remembered the scene in 1 Kings 19, where Elijah is called out of his hiding place in a cave by God:

“Then a great and powerful wind tore the mountains apart and shattered the rocks before the Lord, but the Lord was not in the wind. After the wind there was an earthquake, but the Lord was not in the earthquake. After the earthquake came a fire, but the Lord was not in the fire. And after the fire came a gentle whisper. When Elijah heard it, he pulled his cloak over his face and went out and stood at the mouth of the cave.” (NIV)

Of course God is present to all things, but She cannot be confined to any one of the elements. Having experienced God’s presence so deeply in forests over the years, it was alarming to feel such a sense of despair, and emptiness. But it is true, just as the forest is a place of beauty and life; it is also a place of suffering and death. If God were wholly present to the forest, there would be no distance to cross between us.

As Pope Francis writes in Laudato Si:

“Our relationship with the environment can never be isolated from our relationship with others and with God. Otherwise, it would be nothing more than romantic individualism dressed up in ecological garb, locking us into a stifling immanence” (Laudato Si, 119).

I am most certainly guilty of romanticism, but this phrase, “stifling immanence” keeps coming back to me. God is everywhere present, and hold all things in existence at each moment. But there remains an infinite gap between us.

As I deepen my Lenten journey with prayer, fasting and silence, I am grateful for this lesson, and it has served as rich food in the Desert of Lent this year.

The Prophet Zoroaster. Source: Wikipedia

I recently did an interview with three Zoroastrians who live here in Vancouver. As I was preparing for the interview, I learned the fascinating history of the death rituals practiced by ancient and some modern Zoroastrian communities.

Briefly, Zoroastrians are followers of the teachings of the prophet Zarathustra, or Zoroaster in Greek, who is thought to have lived some time between 1,500 and 650 BCE. They are probably the first monotheistic religions with a great reverence for the elements, especially fire, which is a kind of incarnation of wisdom.

However, because of a dualistic cosmology, with the forces of good and evil forever at odds, dead bodies are believed to be quickly tainted by evil spirits. Because the elements are holy, death must be dealt with in such a way that the elements are not tainted by the corpse. This means no burial, no cremation, or setting out to sea. Traditionally then, Zoroastrians have conducted what is often referred to as ‘sky burial.’ The corpse is taken to a place called a Tower of Silence, where carrion eaters such as vultures devour the corpse. The technical term for this is excarnation, and it is also practiced by certain sects of Tibetan Buddhism, and in Mongolia, Bhutan, and Nepal.

Mumbai Tower of Silence Entrance

Source: Wikipedia

One particular case that drew my attention, was the Zoroastrian community in Mumbai, whose Tower of Silence called the Doongerwadi, is surrounded by 54 acres of unmanaged forest, creating a small oasis. The Tower was built in the late 1600s, but is located in what is now an upper middle class neighborhood.

However, in the 1990s, the vulture population, which traditionally devoured the corpses in short order, collapsed due to the use of a drug administered to cattle, which was then ingested by the birds who had eaten the remains of treated cows. In some places, the vulture population was decreased by 99%.

This decrease in the vulture population, has meant that there are not enough birds to properly decompose the corpses of Mumbai’s Zoroastrian community, and there are worries about the public health implications of half decomposed corpses sitting around, even with the forest buffer.

In response, Zoroastrian activists have begun experimenting. There is a vulture breeding program in the works that is having some success, but others have began experimenting with solar concentrators which direct the suns heat onto the decomposing corpses which dries them out and speeds up decomposition time.

Sources

[Homily delivered Feb. 26, 2017 to Saint Margaret Cedar-Cottage Anglican Church.]

At 4:13 AM I stumbled in the pale darkness to my choir stall. When I finally looked up through the west facing window of the chapel at Our Lady of Guadalupe Abbey in northwestern Oregon, a glowing full moon was setting through a light haze. The monks began to chant the early morning Divine Office of Vigils, a ritual that unfolds day after day, month after month, and year after year in monasteries all over the world.

This month-long immersive retreat in 2014, inspired the questions that would become my PhD dissertation research, which I completed over a six month period in 2015 and 2016. I am now in writing the dissertation, and should be done in the next 2, 3, 4 or 5 months. I wanted to better understand the relationship between the 1,500 year old monastic tradition, contemporary environmental discourses and the land. And I wanted to better describe for the emerging Spiritual Ecology literature the ways that theological ideas and spiritual symbols populate monastic spirituality of place and creation.

In the readings this morning, we are gifted several land-based symbols. God says to Moses in Exodus: “Come up to me on the mountain.” Liberated from Egypt, God is now eager to build a relationship with his people and Moses’s ascent of Mount Sinai to receive the Law mirrors our own spiritual journeys. A thick cloud covered the mountain for six days before Moses was finally called into God’s presence, like so much of my own spiritual life, lived in darkness, with small rays of light.

In the Gospel reading, Jesus too ascends a “high mountain.” There, his disciples witness one of the most perplexing scenes in the New Testament: The Transfiguration. Jesus’s face and garments shone like the sun. And then, certainly conscious of the Hebrew text, the writer says that a bright cloud overshadowed them and they heard a voice say: “This is my Son, the Beloved; with him I am well pleased; listen to him!” Christ, who was fully human and fully God, was revealing in his very person to Peter, James and John his fulfillment of the Law and the Prophets. And presence of the symbols of mountain and cloud were bound up in the authenticity of Jesus’s claims to messianic authority.

Even though it’s not clear that the Apostle Peter is the author of our second reading, the message is clear: “For we did not follow cleverly devised myths when we made known to you the power and coming of our Lord Jesus Christ, but we had been eyewitnesses of his majesty.” Reading Exodus and Matthew, it might feel simple to slip into an easy allegorical hermeneutic, to see everything as a symbol; but the writer of 2 Peter is clear: Stop trying to turn everything into a myth! This reminds me of the quote from Catholic writer Flannery O’Conner who said of the Real Presence in the Eucharist, “If it’s just a symbol, to hell with it.”

With these texts in mind, especially questions of religious symbols and religious realities, I want to talk a little bit about my research with monastic communities, and then return to these texts at the end. Monasticism, like Christianity as a whole is steeped in symbols. For example, the Abbas and Ammas of the early monastic tradition experienced the desert as a symbol of purification and sanctification. Saint Anthony fled to the desert to live a life of solitude, spiritual warfare and strict asceticism. The silence and nakedness of the desert landscape was as it were a habitat for the silence and simplicity that led the Desert Fathers and Mothers through the wilderness of their own sin to the simplicity of God’s presence. As Saint Jerome wrote, “The desert loves to strip bare.”

With these texts in mind, especially questions of religious symbols and religious realities, I want to talk a little bit about my research with monastic communities, and then return to these texts at the end. Monasticism, like Christianity as a whole is steeped in symbols. For example, the Abbas and Ammas of the early monastic tradition experienced the desert as a symbol of purification and sanctification. Saint Anthony fled to the desert to live a life of solitude, spiritual warfare and strict asceticism. The silence and nakedness of the desert landscape was as it were a habitat for the silence and simplicity that led the Desert Fathers and Mothers through the wilderness of their own sin to the simplicity of God’s presence. As Saint Jerome wrote, “The desert loves to strip bare.”

The motifs of the Desert-wilderness and the Paradise-garden are like two poles in Biblical land-based motifs. Pulling the people of Israel between them. Adam and Eve were created in a garden, but driven to the wilderness. The people of Israel were enslaved in the lush Nile Delta, but liberated into a harsh desert. The prophets promised the return of the garden if Israel would flee the wilderness of their idolatry. Christ suffered and resurrected in a garden after spending 40 days in the wilderness. The cloister garden at the center of the medieval monastery embodied also this eschatological liminality between earth and heaven, wilderness and garden.

Mountains too were and continue to be powerful symbols of the spiritual life. From Mount Sinai to Mount Tabor, John of the Cross and the writer of the Cloud of Unknowing, each drawing on the metaphors of ascent and obscurity.

But do you need a desert to practice desert spirituality?

Do you need the fecundity of a spring time garden to understand the resurrection?

I would argue that we do.

For my PhD research, I conducted 50 interviews, some seated and some walking, with monks at four monasteries in the American West. My first stop was to New Camaldoli Hermitage in Big Sur, California. The community was established in 1958 by monks from Italy. The Hermitage is located on 880 acres in the Ventana Wilderness of the Santa Lucia Mountains. Coastal Live Oak dominate the erosive, fire adapted chaparral ecology, and the narrow steep canyons shelter the southernmost reaches of Coastal Redwood. The monks make their living by hosting retreatants and run a small fruitcake and granola business.

The second monastery I visited was New Clairvaux Trappist Abbey, which is located on 600 acres of prime farmland in California’s Central Valley and was founded in 1955. It is located in orchard country, and they grow walnuts and prunes, and recently started a vineyard. They are flanked on one side by Deer Creek, and enjoy a lush tree covered cloister that is shared with flocks of turkey vultures and wild turkeys that are more abundant than the monks themselves. They recently restored a 12th century Cistercian Chapter house as part of an attempt to draw more pilgrims to the site.

Thirdly, I stayed at Our Lady of Guadalupe Trappist Abbey, which was also founded in 1955, in the foothills of the Coastal Range in Western Oregon. When they arrived, they found that the previous owner had clear cut the property and run. They replanted, and today the 1,300 acre property is covered by Douglas fir forests, mostly planted by the monks. Though they began as grain and sheep farmers, today the monastery makes its living through a wine storage warehouse, a bookbindery, a fruitcake business, and a sustainable forestry operation.

For my last stop, I headed to the high pinyon-juniper deserts of New Mexico. At the end of a 13 mile muddy dirt road, surrounded by the Chama River Wilderness, an adobe chapel stands in humble relief against steep painted cliffs. Founded in 1964, Christ in the Desert Abbey is the fastest growing in the Order, with over 40 monks in various stages of formation. The monks primarily live from their bookstore and hospitality, but also grow commercial hops which they sell to homebrewers.

In my interviews, the monastic values of Silence, Solitude and Beauty were consistently described as being upheld and populated by the land. The land was not just a setting for a way of life, but elements which participated in the spiritual practices of contemplative life. To use a monastic term, the land incarnates, gives flesh, to their prayer life.

Thus, the monks live in a world that is steeped in religious symbols through their daily practice of lectio divina, and the chanting of the Psalms. As one monk of Christ in the Desert put it:

“Any monk who has spent his life chanting the Divine Office cannot have any experience and not have it reflect, or give utterance in the Psalmody. The psalmody is a great template to place on the world for understanding it, and its language becomes your own.”

In this mode, the land becomes rich with symbol: a tree growing out of a rock teaches perseverance, a distant train whistle reminds one to pray, a little flower recalls Saint Therese of Lisieux, a swaying Douglas fir tree points to the wood of the cross, a gash in a tree symbolizes Christ’s wounds. In each case, the elements of the land act as symbol within a system of religious symbology. One monk of Christ in the Desert, who wore a cowboy hat most of the time related:

“When the moon rises over that mesa and you see this glowing light halo. It echoes what I read in the Psalms. In the Jewish tradition the Passover takes place at the full moon, their agricultural feasts are linked to the lunar calendar. When they sing their praises, ‘like the sunlight on the top of the temple,’ ‘like the moon at the Passover Feast.’ ‘Like the rising of incense at evening prayer.’ They’re all describing unbelievable beauty. I look up and I’m like that’s what they were talking about.”

The land populates familiar Psalms, scriptures and stories with its elements and thus enriches the monastic experience of both text and land.

Theologically speaking, God’s presence in the land is a kind of real presence that does not just point to, but participates in God. This gives an embodied or in their words, incarnational, quality to their experience of the land. As another example, one monk went for a long walk on a spring day, but a sudden snow storm picked up and he almost lost his way. He related that from then on Psalm 111 that states “Fear of the Lord is the beginning of wisdom” took on a whole new meaning.

In addition, the monks often spoke of their experiences on the land in terms of flashes of insight, or moments of clarity that transcended any specific location or symbolic meaning. One monk called these experiences “charged moments” where a tree or vista one sees frequently, suddenly awakens to God’s presence.

The monks at each community, in their own ways, have sunken deep roots into the lands they live on and care for. Each, in the Benedictine tradition, strive to be “Lovers of the place” as the Trappist adage goes. When I asked one monk if this meant that the landscape was sacred, he paused and said, “I would only say that it is loved.”

I am arguing in my dissertation that monastic perception of landscape can be characterized as what an embodied semiotics. By this I simply mean that symbols and embodied experience reinforce each other in the landscape, and without embodied experience symbols are in danger of losing their meaning.

The motifs of desert and wilderness, the symbols of water, cloud, mountain, doves, bread and wine, the agricultural allegories of Jesus, and the garden, are in this reading, reinforced by consistent contact with these elements and activities in real life.

On the last Sunday before Lent, as we move into the pinnacle of the Christian calendar, it is no coincidence that the resurrection of the body of Jesus is celebrated during the resurrection of the body of the earth. But does this mean that Jesus’s resurrection can be read as just a symbol, an archetype, a metaphor for the undefeated message of Jesus? Certainly Peter and the other Apostles would say no. They did not give up their own lives as martyrs for a metaphor.

For a long time I struggled with believing in the resurrection as a historical reality. But when I began to realize the connection between the land and the paschal mystery, it was the symbols in the land itself that drew me to the possibility of Christ’s resurrection. And that in turn reinforced my ability to see Christ in the entire cosmic reality of death and rebirth active and continual in every part of the universe.

As Peter warns his readers: “You will do well to be attentive to this as to a lamp shining in a dark place, until the day dawns and the morning star rises in your hearts.” For how can we truly believe in the return of the Beloved Son, if we have never been up early enough to see the return of the star we call sun?

Krista Tippet, the gifted radio journalist who hosts the popular On Being radio show and blog, recently published an article in the Jesuit America Magazine. The article is an optimistic assessment of the future of religion in the hands of an increasingly irreligious generation we all know as “Millennials.”

While many are wringing their hands at the decline of religious identity and church attendance among nearly 1/3 of those under 30, Tippet boldly proclaims: “The new nonreligious may be the greatest hope for the revitalization of religion.” Tippet identifies these ‘spiritual but not religious’ with an emerging ‘21st century reformation,’ wherein the traditional markers of Christian or religious identity are shifting, not disappearing. Her comments resonate with writers like Episcopal Priest Matthew Wright or Camaldolese monk Cyprian Consiglio who are calling this shift the ‘Second Axial Age,’ comparing it to first Axial Age, which was responsible for birthing the world’s major religious traditions between 900-300 BCE.

Tippet doesn’t blame many of the young for feeling repulsed by religion. The political debates of the 1980s and 90s were filled with toxic moralizing, culture warriors that hardly seemed to embody the love we were taught was the essence of the God we were supposed to be worshiping. The new forms of religiosity she sees defy many of modernism’s supposed conflicts: New Monastics like Adam Bucko and Rory McEntee are reinventing community and liturgy; curiosity and wonder are transcending the crusty debates between religious and scientific certainty; and a passion for social justice is melting the supposed divide between secular and sacred. She writes:

“I see seekers in this realm pointing Christianity back to its own untamable, countercultural, service-oriented heart. I have spoken with a young man who started a digital enterprise that joins strangers for conversation and community around life traumas, from the economic to the familial; young Californians with a passion for social justice working to gain a theological grounding and spiritual resilience for their work and others; African-American meditators helping community initiatives cast a wider and more diverse net of neighbors. The line between sacred and secular does not quite make sense to any of them, even though none of them are religious in any traditional form. But they are animated by Martin Luther King Jr.’s vision of creating “the beloved community.” They are giving themselves over to this, with great intention and humility, as a calling that is spiritual and not merely social and political.”

The decline in traditional religious observance is a sign of the shape of religion to come, not the death knells of religion as we know it.

Conservative writer Rod Dreher on the other hand, has a different approach. Convinced by Alasdair MacIntyre’s critique of modernity in After Virtue who writes: “What matters at this stage is the construction of local forms of community within which civility and the intellectual and moral life can be sustained through the new dark ages which are already upon us” (my emphasis), Dreher sees Christian culture becoming dangerously thin in the wake of modernity. He thus calls on Christians to adopt the ‘Benedict Option’ or, a communitarian vision rooted in the wisdom of the 1,500 year old Rule of Saint Benedict. He defines it this way:

“The “Benedict Option” refers to Christians in the contemporary West who cease to identify the continuation of civility and moral community with the maintenance of American empire, and who therefore are keen to construct local forms of community as loci of Christian resistance against what the empire represents.”

American Christianity has become to individualistic, too patriotic, and too cozy with the norms and assumptions of modernity. The Enlightenment project created a world of science and democracy, but also of “moral chaos and fragmentation.”

Dreher is not a utopian, or an escapist, but his view of contemporary religious scene differs greatly from that of Tippet. While Tippet is optimistic about the energy and possibility in the rising generation, Dreher seeks to circle the wagons so that Christianity can revitalize itself from within. “Voting Republican, and expecting judges to save us, is over. It’s all about culture now.”

Dreher thus looks to Saint Benedict (480-553), the Italian monk who in the 6th century fled the corruption of a defeated Rome for the solitude of the forest. He eventually gathered a community around him, and wrote his famous Rule. For Dreher, Benedictine monasticism can teach the whole of Christianity many lessons about authentic Christianity, without necessarily requiring that we all become celibate monastics.

He writes, “The monasteries were incubators of Christian and classical culture, and outposts of evangelization in the barbarian kingdoms.” For Dreher and many others, Christianity is not a worldview or system of beliefs, but a way of life. Thus community must begin not just with beliefs and morality but praxis. How shall we live? This means creating community boundaries and norm that form Christians in a way of life. It means balancing work and prayer, but also making our work a prayer. It means not just going to church on Sunday, and then returning to 9-5 job during the week. Dreher also admonishes Christianity to learn the monastic virtue of Stability: or, learning how to stay put, and seeing what places and people have to teach us. We need, Dreher suggests, to learn how to live in community again, because community living informs who we are and what we are called to be.

Dreher and Tippet stake out seemingly opposite assessments of the state and future of religion, particularly Christianity. However, I think that both hit on important tasks for religious culture in the coming years.

In the end, I agree with both Tippet and Dreher, the future of religion is bright, but we can’t all hold the same candle.

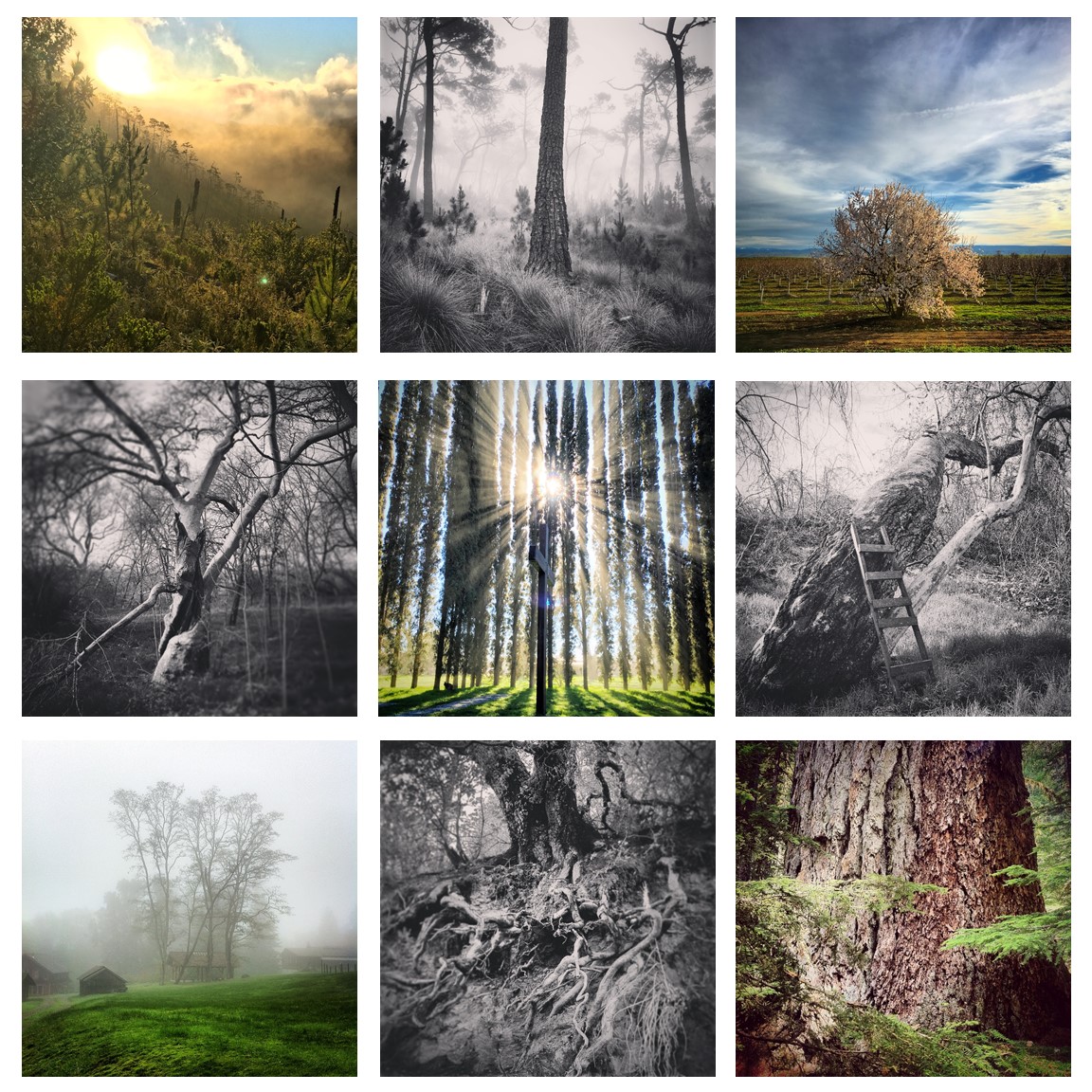

Imagine the most common of trees, the Christmas (or Solstice) tree, decorated with globes, lights and a star on top. Allow that tree to grow in your mind so that it fills the sky.

The bright star at the very top of the tree merges with the North Star, Polaris.

Now imagine that the gold and silver globes become the sun, the phases of the moon, and the other planets moving through the sky, appearing to pivot around the North Star.

Imagine that the twinkling lights are billions and billions of stars.

The Christmas tree is a microcosm of the macrocosm.

The Norse pagans placed the ash tree at the center of their cosmology.

Its sprawling roots descended into the underworld; its trunk and branches passed through the mortal realm, ascending to heavenly.

The Maya imaged the cosmos as a great Ceiba tree, which also descended to the underworld and ascended through thirteen levels of heaven, each level with its own god.

The sun and moon made their way along the Ceiba’s trunk, and the spirits of the dead moved along its rough bark.

The naturalist and pantheist John Muir used to climb to the top of large pine trees during rain storms. About trees and the universe he mused:

We all travel the Milky Way together, trees and [humans]; but it never occurred to me until th[at] stormy day, while swinging in the wind, that trees are travelers, in the ordinary sense. They make many journeys, not extensive ones, it is true; but our own little journeys, away and back again, are only little more than tree-wavings—many of them not so much.

In the beginning, the tree of life emerged as a tiny seedling.

Soon, it branched out into everything we call living: microbes, fungi, plants, trees, animals.

The seeds of humans germinated in the trees.

Our mammalian and primate ancestors made their homes in their bows.

Eventually, our curiosity compelled us down from the safety of their branches and out onto the savanna.

Yet, the trees never left us;

They continued to provision us with gifts on our long walks.

They gave food, fodder, shelter, tools, medicine and stories.

They appeared in our dreams.

It was here, in a forest, that Zoroaster in Persia saw the Saena Tree in a vision emerging from the primeval sea, a tree from whose seeds all other plants would grow.

It was here that Yahweh, Semitic sky god, came to earth and planted a garden of trees, pleasing to the eye and good for food.

It was here that Inanna, Babylonian goddess of beauty and love, nourished the Huluppu tree on the banks of the Euphrates River.

It was here that Kaang, creator god of the Batswana Bushmen, created the first mighty tree and led the first animals and people out from the underworld through its roots and branches.

It was here that the sacred tree gave light to the Iroquois’s island in the sky—before the sun was made, before Sky Woman fell through a hole in the island in the sky, and before the earth was formed on the back of a great turtle.

It was here that the Mayan Tree of Life lifted the sky out from the primordial sea, surrounded by four more trees that hold the sky in place and mark the cardinal directions.

It was here, in a forest, that the first whispers of the divine spoke to human consciousness.

It was here that Jacob wrestled with angels and beheld visions.

It was here that Hindu seekers learned the wisdom of gurus.

It was here, seated beneath the Bodhi tree, that Siddhartha Gautama became the Buddha.

It was here that Moses fasted, prayed, and received God’s Law.

It was here that Muhammad sought refuge in mountain caves and spoke the words of the holy Koran.

It was here that Guru Nanak experienced the Oneness of God.

It was here that Nephi of the Book of Mormon communed with angels and beheld the glorious fruit of the Tree of Life.

It was here, in a forest, that we built our first temples and worshipped God without priesthoods.

It was here that Asherah, Canaanite goddess of all living things, was worshipped.

It was here, as Sycamore fig, that Isis of Egypt was lavished praise.

It was here, in grove of sacred oak, that the Druids passed on their knowledge, and sacrificed human flesh to the gods.

It was also here, in the forest, that, after civilization blossomed, we looked for inspiration—

Temples of stone with their pillars, columns, and cathedral arches were all made to resemble the trunks of trees, carrying the eye upward to God.

And yet, it would seem that these temples of stone confined God to one place, one people, one faith.

It was here that we fell from grace.

It was here that Adam and Eve ate the fruit of a misunderstood tree.

It was here that civilization bloomed.

It was here that we logged, burned, mined, clear-cut, developed.

It was here that the old stories were forgotten and new ones were written;

Stories in which creation was no longer sacred, enchanted, animate, subjective.

Return

In an age of climate chaos and heart breaking extinction, it is here, to the forest, that we must return.

Not only as skiers, hikers, campers, birders, hunters, and foresters, but as devotees.

Because it is here that we see the universe in microcosm, where we get our bearings.

It is here that creation awes.

It is here that we experience the divine.

It is here that we can bring our questions.

It is here that we can dwell in mystical solitude.

It is here that we are now—The global forest.

To return to the forest, we must become familiar with it.

I invite you to go to a mountain grove or a city park and take off your shoes.

When you are comfortable and alone, close your eyes.

Begin by focusing on feeling—as a tree might—the sun, the wind, the earth beneath your toes and on your skin.

If you wish, stretch your arms up and out like branches seeking the light.

Imagine drinking in the caramel rays of the sun as nourishment.

Focus on your breath by letting the air pass through your nostrils and fill the arboreal-patterned branches in your lungs.

Feel your lungs slowly fill with oxygen.

Feel them slowly empty as your body expels carbon dioxide.

Focus on the entire process of breathing and how each moment changes.

In and out.

As you breathe in, imagine that the oxygen, conceived in the leaves of trees, is gently birthed from the leaf’s stomata, wafting through space, and entering your lungs.

As you breathe out, imagine that the CO2, re-born in your lungs, is gently wafting through the air and entering the receptive stomata of the leaves.

In and out.

The air becomes us, becomes them.

It is a sacrament; we take it upon us, into us, and they upon themselves.

As we breathe in, the trees breathe out.

As the trees breathe out, we breathe in.

We are their lungs and they are ours.

In and out.

This is not a supernatural idea; it is an ecological reality.

May we dwell in this reality!

The mystic monk and (one time monastery forester) Thomas Merton said:

We are already one. But we imagine that we are not. And what we have to recover is our original unity. What we have to be is what we are.

What we are is not all that different from trees.

And so I offer you this prayer for your walks and sits among the trees.

Forest, Trees. May we sustain you as you sustain us.